Tucked away in the humid mountain folds of southern China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Liu Bao tea has spent four centuries quietly fermenting while its more famous cousins—Pu-erh, Fu Brick, and Qian Liang—dominated the dark-tea limelight. Yet for those willing to listen, Liu Bao whispers stories of horse caravans, maritime tea routes, and bamboo-lined cellars where time itself is brewed into every leaf.

- From Border Tribute to Maritime Gold

Liu Bao’s recorded history begins in the late Ming dynasty, when the small town of Liu Bao (literally “Six Forts”) in Wuzhou prefecture served as a military outpost guarding the trade corridor between the Han heartland and the southern tribes. Local tea growers discovered that the coarse summer leaves, too bitter for green-tea standards, transformed into a mellow, digestive tonic after months of steaming, piling, and bamboo-basket storage. By the Qing Qianlong era (1736–1795), Liu Bao had become one of the “Three Tribute Teas of Guangxi,” shipped north to the imperial court along the Xun River.

The real turning point came in the nineteenth century when British and Hong Kong traders re-routed Liu Bao through the Pearl River Delta to Southeast Asia. Malayan tin miners and rubber tappers prized the tea for dissolving grease and preventing malaria; dockside warehouses in Singapore and Penang became accidental aging cellars, where the tea absorbed the salty humidity and acquired a caramelly, betel-nut sweetness that distinguished it from the earthier Pu-erh. Today, vintage 1970s Liu Bao fetches higher prices in Kuala Lumpur than in Beijing, a living testament to diaspora taste.

- One Leaf, Three Styles

Although all Liu Bao is dark tea, the micro-categories reflect both processing intensity and storage philosophy:

- San Cha (loose leaf): The most common export style, lightly pile-fermented for 30–40 days, then sun-dried and packed into 50 kg rattan baskets. Drunk young, it tastes of dried longan and wet slate; after ten years in a humid climate, it darkens to prune and camphor.

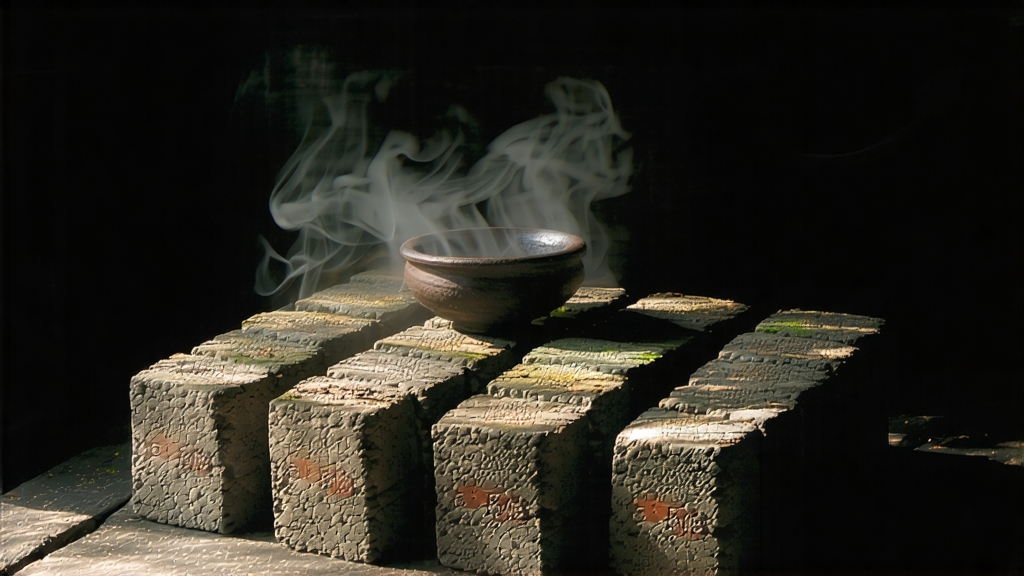

- Basket Brick (Lan Zhuan): The same leaf steamed and compressed into 2–5 kg “bricks” lined with bamboo leaves. The compression slows oxidation, creating a layered profile: top notes of pine honey, base notes of leather and tobacco.

- Aged Loose (Chen Xiang): Leaf stored unsealed in clay jars or wooden chests for twenty-plus years. Microbial activity concentrates theaflavins into a ruby liquor that smells like vintage Madeira and finishes with a cooling menthol lift.

- Crafting Time in a Pile

Liu Bao’s production calendar begins in late May, when the subtropical sun coaxes out the third and fourth leaves—mature, leathery, and rich in pectin. After a brief outdoor withering to reduce grassy volatiles, the leaves are wok-fired at 280 °C for exactly 90 seconds; this “killing green” step arrests polyphenol oxidase but preserves heat-resistant spores of Aspergillus niger and Blastobotrys adeninivorans, the microbial workhorses of later fermentation.

The pivotal operation is “wet piling” (wo dui), Guangxi’s humid answer to Pu-erh’s yu wo. Workers sprinkle 28 °C mountain water over 500 kg leaf piles, then cover them with jute sacks and banana leaves. Internal temperature is monitored like a soufflé: when the core hits 55 °C, the pile is turned to aerate and prevent anaerobic spoilage. Over six weeks, the leaf color shifts from army green to dark umber, while bitter catechins polymerize into mellow theabrownins and novel pigments called liubaochromes—unique reddish compounds that give aged Liu Bao its signature coppery rim in the cup.

Post-fermentation, the tea is sun-dried on bamboo screens for three days, then moved to “returning green” rooms where it rests at 75 % humidity and 30 °C for another month. This seemingly idle interval allows residual microbes to “polish” rough edges, much like malolactic fermentation softens young wine. Finally, the leaf is sorted into grades—first, second, and third—