Few beverages carry the quiet mystique of Fu brick tea. To the uninitiated it looks like a dusty grey building block, wrapped in rough straw paper and stamped with cryptic Chinese characters. Yet once the wrapper is peeled away the brick reveals a constellation of tiny golden speckles—microscopic blossoms that Chinese merchants once called “the gold that grows.” Those blossoms, a beneficial mold named Eurotium cristatum, are the signature of Fu brick, the only tea whose value is measured by how brightly it can bloom.

A child of the ancient Silk Road, Fu brick was born from urgency. During the early Ming dynasty (1368-1644) the imperial court banned the traditional practice of pressing loose Hunan maocha into cumbersome 35-kilogram “Jian” logs for transport to the frontiers. Caravans needed something lighter, faster to unload, and less prone to theft. Tea masters in the humid lake-region of Anhua began compressing partially dried leaves into smaller 2-kilogram bricks, but the humid summer caravans triggered accidental fermentation. Months later, when the bricks reached the Tibetan plateau and the Mongolian steppe, drinkers noticed a mellow, hay-sweet liquor that calmed stomachs soured by yak butter and mutton fat. The accident became a recipe; the recipe became Fu brick, named after the county of Fushun in Shaanxi where the bricks were first warehoused and traded.

Today the geography remains narrow and fiercely protected. Only three valleys along the Zi River in Hunan—Anhua, Taojiang and Yuanjiang—supply the raw leaf. The cultivar is Yun-Tai Da-Ye, a large-leaf landrace that accumulates unusually high levels of flavonoids and soluble pectin, the very compounds Eurotium needs to weave its golden web. Harvest begins at Qingming festival when the first three leaves unfurl. Pickers snap the stem at the fourth node, ensuring enough lignin to keep the brick intact under 20 tons of hydraulic pressure later on.

The craft unfolds in four slow acts: fixation, rolling, piling, and flowering. Fixation is brief—just three minutes in a 280 °C drum—to kill green enzymes while preserving leaf toughness. Rolling is done barefoot on bamboo mats; the foot’s arch exerts even pressure that cracks cell walls without shredding the leaf. Next comes the critical “wet piling,” a 12-hour sauna in which 200-kg heaps are sprayed with 28 % moisture and covered by hemp cloth. Inside this compost-like core the temperature climbs to 55 °C, triggering a microbial relay: first yeasts, then lactic acid bacteria, finally Eurotium spores that drift invisibly from the rafters of old wooden warehouses. When the pile emits a faint apricot aroma workers know the fungus has taken hold. The tea is then dried to 14 % moisture, steamed for 90 seconds at 102 °C, and pressed into iron molds lined with hand-woven straw. The bricks spend the next month in a dark 28 °C “flowering room,” where humidity hovers at 75 %. By day 20 the golden flowers—bright yellow dots no larger than a pinhead—cover up to 90 % of the brick’s cross-section. A second desiccation drops moisture to 9 %, locking the living culture into a dormant state that can survive decades.

Unlike pu-erh, Fu brick does not rely on regionality alone for its aging potential. Eurotium continues a quiet metabolism, converting starches into rare polyketides that impart a cooling camphor note after ten years, and a deep dried-jujube sweetness after thirty. Connoisseurs speak of “three blooms”: the first at production, the second after seven years when liquor turns amber, and the third after twenty when the brick exudes a faint whisper of orchid and antique parchment.

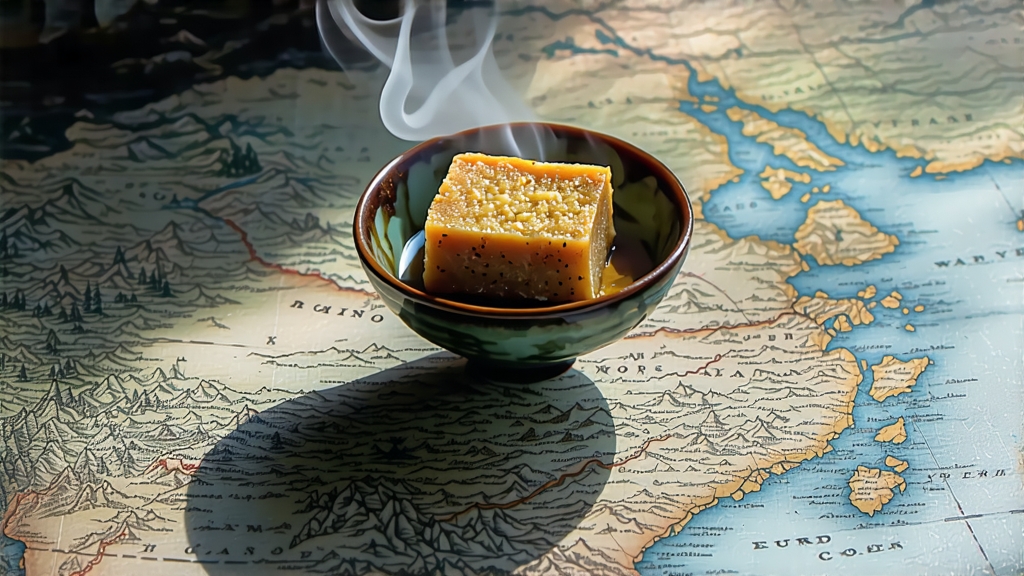

To brew Fu brick is to coax a dormant ecosystem back to life. Begin by breaking, not cutting. A stainless pick inserted at a 45° angle lifts a 5-gram flake while preserving the flower layer. Rinse with 100 °C water for only three seconds; longer washes strip the precious spores. The first proper infusion needs a violent wake-up: 100 °C water poured from 15 cm above the gaiwan lip, creating a foam of tiny bubbles