Deep in the karst hills of southern China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, a tea has been quietly fermenting for centuries, absorbing the humidity of subtropical forests and the smoke of camphor-lined storerooms. Liu Bao—literally “Six Forts”—is the least-known yet most aromatic member of China’s dark-tea family. While Pu-erh commands auction headlines and Fu brick dazzles with its golden “flowers,” Liu Bao travels in battered bamboo baskets, its rough leaves coated in a dusty bloom that smells of damp earth, dried longan, and the faint sweetness of betel nut chewed by dock workers along the once-bustling Tea Road to Southeast Asia. To the international palate, Liu Bao is both familiar and strange: the comforting malt of Assam married to the forest funk of a Bordeaux barrel room. Understanding it means stepping into a microclimate where tea is not merely processed but lived with, aged beside rice wine jars and herbal medicines until it becomes a living archive of place and time.

History: From Border Garrison to Maritime Currency

Liu Bao’s story begins during the Ming dynasty’s consolidation of the southern frontier. In 1567 the imperial court designated Cangwu County as a tea-tax collection point, demanding compressed leaf as payment for garrison salaries. Locals discovered that the humid march to the forts transformed the tea: green harshness mellowed into a deep, sweet liquor that calmed fever and digested the oily river fish that fed soldiers. By the Qing era, Liu Bao had become ballast aboard junks sailing the Pearl River delta. Reaching Malacca, Penang, and Jakarta, it was bartered for pepper, nutmeg, and opium, earning the nickname “coolie currency” because plantation workers were partly paid in bricks of Liu Bao believed to prevent beriberi. When the British moved tea cultivation to Ceylon and India, Liu Bao’s export route collapsed; the tea retreated into provincial memory, hoarded by miners and herbalists who valued its ability to “cut grease” after meals of rice congee and river snails. Only in 2006, when China applied for UNESCO recognition of the Ancient Tea Road, did Liu Bao re-emerge, its bamboo baskets reopened to reveal leaves that had been breathing for four decades.

Terroir and Leaf Styles

Guangxi’s low-latitude highlands deliver year-round fog and diurnal swings of 10 °C, ideal for the large-leaf Camellia sinensis var. assamica that migrated from neighboring Yunnan. Three micro-zones define Liu Bao character:

- The limestone gorge around Liubao town produces narrow, charcoal-black leaves with a camphor coolness.

- The red-basin hills of Tengxian yield broader leaves rich in catechins that ferment into cocoa notes.

- The granite peaks of Mengshan give mossy, orchid-tinged teas prized by Hong Kong cellars.

Within each zone, pickings are graded by maturity: yi ji (first grade) combines one bud with two leaves for a bright, honeyed cup; san ji (third grade) uses three-to-four leaves, packing more tannins for decades of aging; cu cha (rough tea) includes stalks and yellow leaves that once cushioned bricks on long voyages, now sought by connoisseurs for their rustic sweetness.

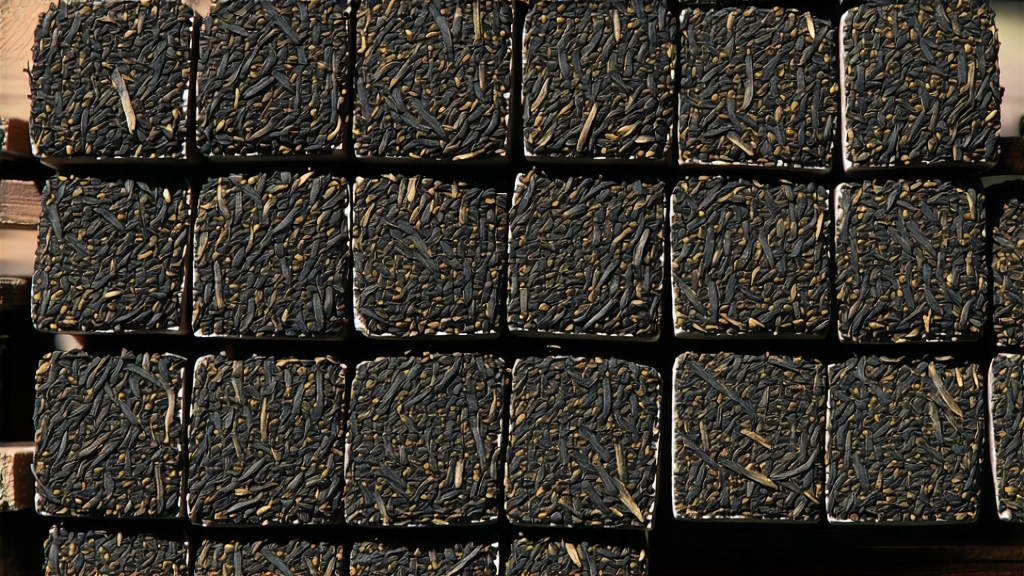

Craft: The Secret 24-Hour Pile

Unlike Pu-erh’s sun fixation, Liu Bao is killed-green in a charcoal-heated iron wok at 280 °C for exactly three minutes, hot enough to blister leaf edges and lock in a smoky signature. While still warm, the leaf is rolled into tight cords that crackle like dry kindling. The critical step is “dui zi”—a controlled 24-hour wet piling unique to Liu Bao. Workers cover 200 kg heaps with wet jute sacks, maintaining 28 °C and 85 % humidity. Indigenous microbes—Bacillus subtilis, Aspergillus niger, and the yeast Pichia fermentans—proliferate, oxidizing catechins into theaflavins and thearubigins that tint the liquor blood-amber. Every two hours the pile is turned by bare hands; the scent evolves from steamed edamame to fermented soy to dark chocolate. When the leaf core cools to ambient temperature, it is sun-dried for half a day, then moved to a