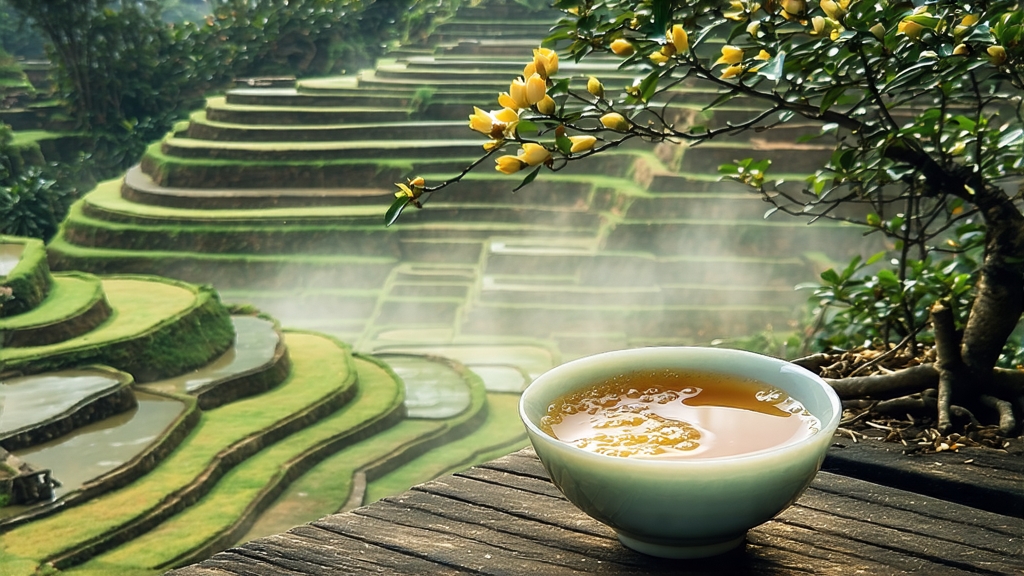

Tucked high above the Sichuan basin where the Min River carves clouds into stone, Meng Ding Huang Ya has been quietly perfecting its golden alchemy since the Tang dynasty. Foreign tea atlases often relegate yellow tea to a footnote between green and oolong, yet this single-bud strand from the legendary Meng Ding Shan—“the misty peak that nurtures ten thousand immortals”—carries within its downy tips the memory of imperial tribute, the craft of sealed yellowing, and a flavor so elusive that Chinese poets once described it as “a moonbeam caught in bamboo.” This article invites the global tea traveler to rediscover Meng Ding Huang Ya through its history, micro-terroir, painstaking micro-fermentation, and the gentle brewing rituals that coax its orchid-honeyed soul into the cup.

-

Historical tapestry

Meng Ding Shan, 1 456 m above sea level, was already cloaked in tea gardens when Lu Yu penned The Classic of Tea (760 CE). Court chronicles of the Song dynasty record that monks of the Ganlu Temple selected the earliest spring buds, steamed them on bamboo trays, and sent the finished tea down-river to Chengdu, where imperial couriers rushed it to Chang’an on horseback. By the Ming, the leaf had evolved from compressed cakes to loose yellow buds, and the Qing emperor Kangxi famously exempted Meng Ding from land tax in exchange for an annual gift of “three liang of golden shoots.” The 20th century’s wars and the later dominance of green tea export nearly erased the craft, but a 1979 state-led restoration project re-established the plucking standard—one open bud or bud-and-single-leaf—reviving yellow tea for a new generation. -

Terroir and cultivar

The mountain’s unique “three clouds a day” phenomenon—morning mist, noon fog, evening haze—filters sunlight into a soft, diffused glow ideal for slow amino-acid accumulation. Granitic soils rich in potassium and selenium feed the local small-leaf Camellia sinensis var. sinensis clone known as “Meng Ding early yellow,” whose tender shoots naturally contain 5.2 % L-theanine, almost double that of valley bushes. The combination of cool nights (8–12 °C) and warm days (18–22 °C) in late March produces buds that are pale jade on the outside yet sun-kissed yellow at the core—nature’s first hint of the transformation to come. -

Craft: the six acts of sealed yellowing

Unlike green tea’s quick kill-green, Meng Ding Huang Ya undergoes a six-step choreography where oxidation is not arrested but guided into a controlled micro-fermentation unique to yellow teas.

a. Plucking: between Qingming and Guyu, only buds 12–18 mm long are nipped with fingernails to avoid the bruising that scissors impart.

b. Withering: the buds are laid on hemp cloth in shaded bamboo pavilions for 120 minutes, losing 8 % moisture and developing a faint grassy bouquet.

c. Kill-green: wok temperatures are kept at an unusually low 140 °C for four minutes; the goal is to denature polyphenol oxidase while preserving a 35 % residual moisture that will later feed the yellowing.

d. Rolling: the warm buds are hand-rubbed for six minutes along the length of the leaf, breaking 30 % of cell walls to release sticky amino acids.

e. Sealed yellowing: the critical signature step. The rolled buds are wrapped in double layers of handmade yellow kraft paper, then buried in a 25 cm-deep wooden chest lined with wet rice straw. Every 40 minutes for the next six hours the master opens the bundle, fluffs the leaves, and re-wraps, allowing a gentle re-oxidation that edges the leaf color from green to primrose. Temperature is maintained at 32 °C and humidity at 78 %—conditions that encourage the growth of flavobacterium and candida parapsilosis, microbes that convert catechins into theaflavins and create the tea’s hallmark “mellow yellow” liquor.

f. Low-temperature drying: finally, the leaves are baked at 55 °C for 90 minutes on bamboo sieves suspended over a charcoal ember of local cedar wood, reducing moisture to 5 % while imbuing a whisper of resinous sweetness.

- Leaf appearance & aroma

Finished