Tucked high in the mist-veiled Dabie Mountains of western Anhui Province, Huoshan Huangya has been whispered about in Chinese tea circles for more than fourteen centuries. Foreign drinkers often greet the name with a polite nod, mistaking it for yet another green tea, yet the moment the liquor touches their lips they fall silent: there is a round, almost creamy sweetness that green tea seldom achieves, followed by a faint scent of fresh chestnut and orchid that lingers like mountain mist. This is the hallmark of a true yellow tea—China’s rarest mainstream category—and Huoshan Huangya is its most aristocratic representative.

Historical scrolls from the Tang dynasty (618-907) already list “Huozhou yellow buds” as tribute tea, carried on bamboo sedan chairs down the mountain to the imperial court. During the Ming dynasty the tea vanished from palace records when the emperor, in a fit of frugality, slashed tribute quotas; farmers turned to more prosaic green teas to survive. It was not until 1972, when a team of Anhui agronomists rediscovered ancient withering chambers hidden behind a Taoist monastery on Jinji Mountain, that the original processing protocol was pieced back together from oral fragments and dusty stele inscriptions. The revived tea entered the state banquet menu in 1976, served to Richard Nixon during his second visit to China, and quietly regained its former prestige.

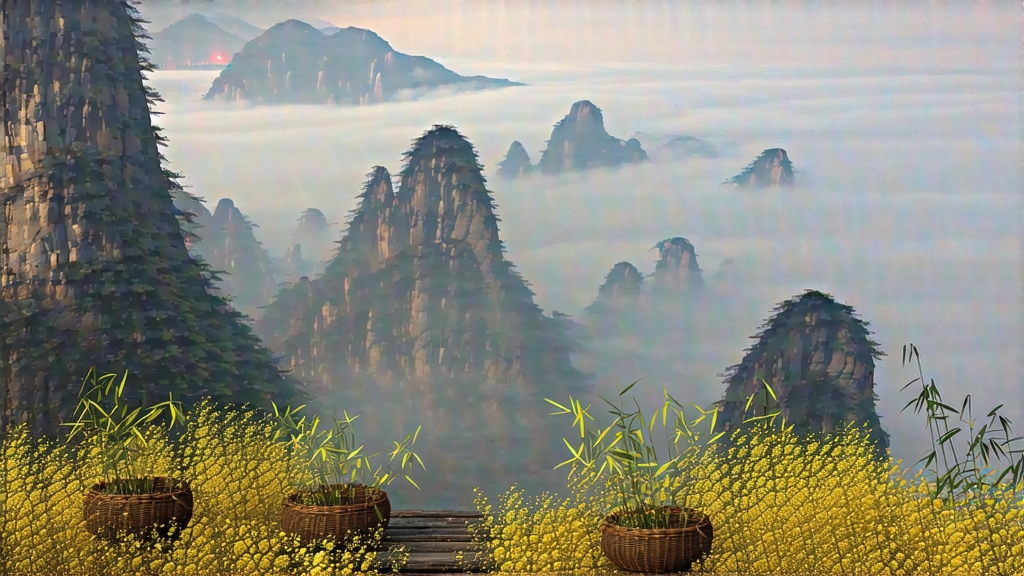

Huoshan County enjoys a perfect crucible for yellow buds: granitic soils laced with quartz, 1,200 mm of rain a year, and a vertical temperature swing of 10 °C between day and night. The local cultivar, Huoshan Da Yezhong, develops unusually thick cell walls; when the leaves are subjected to the hallmark “menhuang” (sealed yellowing) step, they oxidize slowly from the inside out, acquiring a golden hue without surrendering the freshness of spring.

Picking begins in the last week of March, just before Qingming festival, when the bud still wears a single unfolded leaf—what locals call “sparrow’s tongue with flag.” A skilled plucker can gather only 400 g in a morning; 50,000 such sets yield one kilogram of finished tea. The harvest must reach the factory within two hours, before the mountain chill warms into grassy astringency.

Processing unfolds like a ritual dance across three nights and two days. First, the leaves are pan-fired at 160 °C for three minutes—long enough to kill the green enzymes, short enough to keep the bud intact. While still warm they are rolled on bamboo mats into tight strips, then piled in oak boxes lined with wet cloth. Here begins the secretive menhuang phase: the boxes rest in a 28 °C, 85 % humidity chamber for 4–6 hours, during which chlorophyll quietly degrades into pheophytin, polyphenols dimerize, and a buttery aroma rises that tea masters liken to warm rice custard. The pile is turned every forty minutes to prevent composting; one lapse and the entire batch collapses into sour hay. When the leaves have turned the color of old gold, they are given a second, gentler firing at 80 °C to lock in the new chemistry, then baked over charcoal embers in bamboo sieves for three nights until only 5 % moisture remains. The final leaf is slim, canary-yellow with a downy silver tip; when snapped it releases a note that is half orchid, half roasted chestnut.

To brew Huoshan Huangya you need calm water and steady hands. Begin with a tall, thin-walled glass or a porcelain gaiwan of 150 ml; metal will flatten the aromatics. Water should be low in minerals—TDS around 30 ppm—and cooled to 80 °C. Use 3 g of leaf, or roughly two heaping teaspoons. Awaken the buds with a 20-second rinse, pouring the water in a high, thin stream so that the leaves tumble like confetti. Discard this liquor; it carries only dust and charcoal breath. First infusion: 45 seconds, water poured along the rim to avoid scalding the tips. The liquor emerges the color of light chardonnay, releasing a bouquet of lily, sweet corn and a trace of pine smoke. Second infusion at 35 seconds deepens the color to old gold; the taste acquires a lanolin texture reminiscent of white peaches. Third infusion at