White tea is the most lightly processed of all China’s six great tea families, and within that minimalist realm Bai Hao Yin Zhen—literally “White-Hair Silver Needle”—stands as the aristocrat. Composed only of unopened leaf buds plucked for a few fleeting mornings each spring, it is tea reduced to its luminous essence: aroma of mountain dawn, flavour of drifting cloud, finish that lingers like a half-remembered poem. To international drinkers accustomed to the roar of black tea or the green flash of sencha, Silver Needle offers a different grammar of pleasure: quiet, spacious, almost ethereal. This essay invites you into that quietness, tracing the cultivar’s history, the invisible craft that shapes it, and the gentle rituals that coax its subtle voice into song.

-

Historical echoes

The written record of “white down tea” appears as early as the Song dynasty (960-1279), when court scholars praised buds “silver as frost, light as goose down.” Yet those cakes were steamed, pressed, and perfumed with jasmine—far removed from today’s loose, withered buds. The modern incarnation took shape in the 1790s around Taimu Mountain, northern Fujian, where tea makers discovered that buds left simply to air-dry could yield a liquor both sweet and cooling. Export firms in Fuzhou shipped the novelty to Europe in lacquered tins; Victorian ladies sipped it for complexion, poets for inspiration. During the 20th-century wars the trade withered, but in the 1990s a new generation, armed with better hygiene and temperature control, revived the craft. Today Silver Needle is protected under China’s Geographic Indication system; buds sold as authentic must be picked within the three-town radius of Yueyang, Fujian, and meet strict standards of length, down density, and moisture. -

The bud as universe

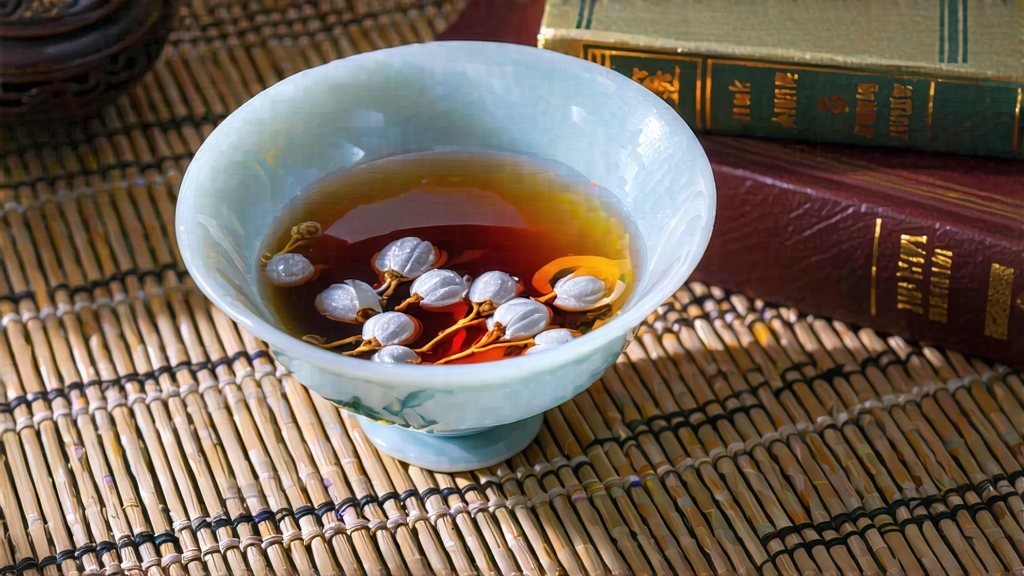

A perfect Silver Needle bud measures 1.5–2.5 cm, plump as a quill yet tapered like a miniature spear. Ten thousand of them yield barely half a kilo of finished tea. Each is wrapped in a duvet of white trichomes—tiny hairs that scatter light, giving the dried tea its moonlit shimmer. Beneath the down lies a storehouse of amino acids (notably theanine), low levels of catechins, and a whisper of caffeine. The result is a liquor that calms without sedating, refreshes without jolting. Because only the apical bud is used, the leaf’s photosynthetic “edge” is absent; flavour arrives not from green bitterness but from the plant’s embryonic sweetness. -

Micro-terroirs

Purists recognise three micro-terroirs within the GI zone. Taimu Mountain, granitic and mist-locked, gives buds of high fragrance and cool minerality. Lower-elevation Houmu gardens yield broader buds with creamier body. The coastal strip around Qinyu, brushed by salt-laden monsoons, produces a variant sometimes called “marine silver,” prized for a faint seaweed umami. Though all qualify as Silver Needle, experienced tasters can blind-identify origin by aroma alone: Taimu like mountain orchid, Houmu like warm rice milk, Qinyu like drifting ozone. -

Craft: the art of doing almost nothing

Harvest begins at dawn when the thermometer hovers between 14 °C and 19 °C and relative humidity tops 70 %. Pickers wear cotton gloves to avoid bruising the cuticle; buds drop into bamboo creels lined with banana leaf. Within two hours they reach the withering loft—an airy pavilion whose walls are latticed pine and whose roof is translucent tile. Here the buds are spread one layer deep on woven bamboo trays. For 36–48 hours they simply rest, exhaling grassy moisture, inhaling mountain breeze. The master’s sole interventions are to shuffle trays so every bud tastes the same moonlight, and to adjust louvers when the mountain wind grows too strong. Finally the buds pass to a low-temperature dryer (35–40 °C) for 15 minutes, just enough to lock moisture at 5 % without toasting the hairs. No rubbing, no rolling, no firing—white tea is tea that refuses to be tea in the conventional sense. -

Grading and ageing

Unlike green tea, Silver Needle improves—and changes—over years.