Few leaves carry as much myth, craftsmanship, and aromatic paradox as Tie Guan Yin, the “Iron Goddess of Mercy.” To the uninitiated it is simply another Chinese oolong; to the adept it is a liquid manuscript recording five centuries of Anxi terroir, Buddhist folklore, and relentless artisanal refinement. This essay invites the global tea lover to step beyond the label and meet the cultivar, the soil, the charcoal ember, and the quiet gaiwan that together conjure one of the world’s most captivating infusions.

- Myth and Historical Strata

Legend places Tie Guan Yin’s birth during the Yongle period (1403-1424) of the Ming dynasty. A devout farmer named Wei Yin daily cleaned a neglected Guanyin shrine in Anxi’s Songyan village; one night the Bodhisattva appeared in a dream, directing him to a hidden shrub glowing in the moonlight. Wei transplanted the bush, nurtured it, and from its leaves produced a tea so fragrant that neighbors believed the iron statue of Guanyin herself had bestowed her essence. Whether apocryphal or not, the tale encodes key cultural genes: reverence, perseverance, and the conviction that tea can embody spiritual presence.

By the Qing Qianlong era (1736-1795) Tie Guan Yin had become imperial tribute, traveling from the granite peaks of Anxi to the Forbidden City in tightly pressed lead-lined tins. Maritime trade routes later ferried it to the docks of London, Penang, and San Francisco, where 19th-century connoisseurs christened it “Iron Buddha,” sensing both its weighty texture and transcendent aroma. Today Anxi County, Fujian, still anchors 60 percent of global production, yet micro-terroirs within the county—Xiping, Gande, Longjuan—have emerged as boutique appellations comparable to Burgundy’s climats.

-

Botanical Identity and Terroir

Tie Guan Yin is a clonal cultivar (Camellia sinensis var. sinensis ‘Tie Guan Yin’) that behaves like a prima ballerina: dazzling on its native stage yet stubborn elsewhere. The plant is medium-leaf, semi-erect, and particularly rich in aromatic precursors such as geraniol and indole. Anxi’s red-granite soil, 800–1,200 m elevation, and subtropical monsoon climate create a diurnal swing of 10 °C, coaxing the leaves to stockpile soluble sugars while slowing catechin development—chemical choreography that translates into the cultivar hallmark of thick, orchid-sweet liquor with minimal astringency. -

Crafting the Iron Goddess

Modern Tie Guan Yin is not a single tea but a spectrum of styles whose personality is written during 36 hours of meticulous processing. The journey begins with a noon pluck of the “open face” standard—three leaves and a bud—when cell turgor is optimal. Sun-withering for 20 minutes lowers moisture to 68 percent, activating grassy lipoxygenase pathways. Leaves are then rocked in bamboo tumblers, a kinetic massage that bruises leaf edges while keeping veins intact; this partial rupture invites ambient enzymes to oxidize catechins into theaflavins and thearubigins, generating the honeyed peach hue that will later crown the cup.

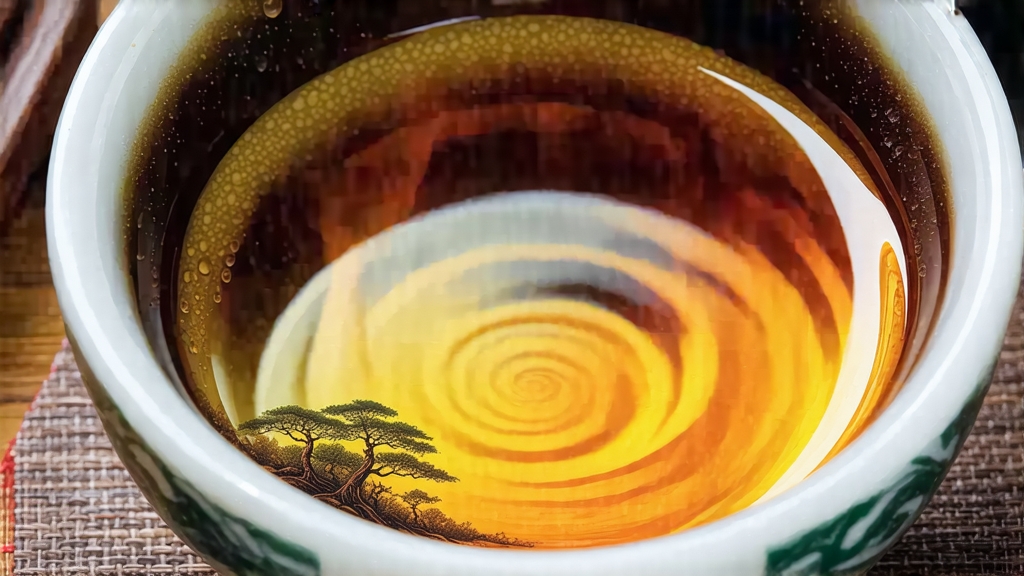

Oxidation is halted at 30–50 percent by a 280 °C tumble in gas-fired drums, locking in a green core wrapped in a bronze perimeter. The critical “wrapping and rolling” step follows: 15 kg of warm leaves are wrapped in white cotton cloth, compressed into a ball, and rolled under a 40 kg stone slab. This bruise-tighten cycle is repeated 30–35 times over two hours, extruding sap that will crystalize into the shiny sandy grains seen on finished strips. Finally, a low 70 °C bake for three hours reduces moisture to 3 percent while Maillard reactions imprint roasted hazelnut notes.

Two style poles dominate today’s market. “Qing Xiang” (light fragrance) is the fashion of the last two decades: minimal baking, electric-green leaves, and a soaring lilac bouquet. “Nong Xiang” (traditional roast) returns to the charcoal embers of the 1980s, undergoing 30-hour gentle charcoal fires in bamboo baskets every two months for up to two years, yielding mahogany strips, cocoa depth, and a lingering y