Tucked between the mist-laden hills of Dongting East Mountain and the gentle shores of Lake Tai in Jiangsu Province, Biluochun—literally “Green Snail Spring”—has captivated Chinese tea lovers since the late Ming dynasty. International drinkers often meet it as a curiosity: tiny, spiral-shaped leaves that smell more like a basket of ripe orchard fruit than the grassy stereotype of green tea. Yet behind its delicate appearance lies one of China most intricate terroirs and labor-intensive crafts. To understand Biluochun is to glimpse the Chinese obsession with capturing the very breath of spring in a single cup.

Historical whispers place the tea’s birth around 1675, when a tea picker in the Dongting hills is said to have filled her basket so high that leftover leaves had to be tucked between her breasts; body heat released an intoxicating perfume that alerted a passing monk. Whether apocryphal or not, the story signals the tea’s signature trait: an aroma so intense it seems almost floral. The Kangxi Emperor (r. 1661-1722) reputedly renamed the originally undignified “Xia Sha Ren Xiang” (“Scary Fragrance”) to the more elegant “Biluochun” after its snail-shell shape and early-spring harvest. Imperial favor pushed the tea into tribute status, and Suzhou scholars soon composed poems claiming that one sip could “cleanse the marrow of city dust.”

Strictly speaking, only leaf plucked within the 12-km core zone around Dongting East and West Mountains can claim the protected geographical indication “Original Biluochun.” Here, the lake acts as a vast heat reservoir, delaying morning warming and extending evening humidity. Peach, plum, and loquat trees are interplanted among tea bushes; their blossoms drop petals that decompose into aromatic mulch, while bees shuttle between fruit and tea flowers, adding invisible esters to the leaf surface. The result is a natural “fruit-bloom” note impossible to replicate on flat plantation land outside the lake basin.

Plucking begins when the tea bush’s first apical bud reaches 1.5–2 cm, usually between the Qingming and Grain Rain solar terms (early April). The standard is one bud plus one unfolding leaf, about 2.5 cm long, weighing 0.2 g apiece. A skilled picker can gather 600 g of fresh leaf in an hour; it takes 55,000 such snippets—an entire day’s work for five people—to yield 500 g of finished tea. Picking is suspended the moment dew dries, because surface moisture would scorch in the wok and flatten the curl.

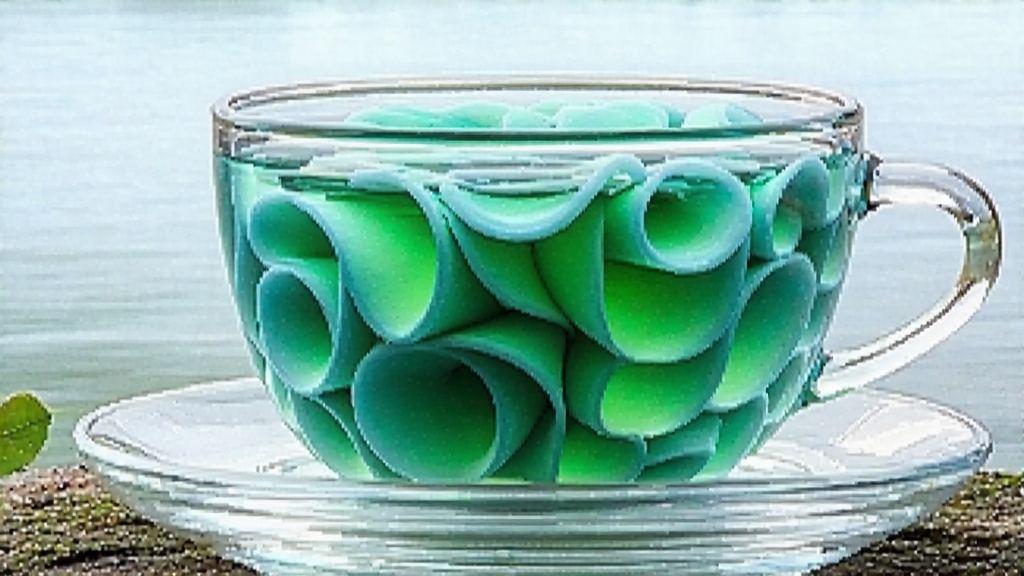

The craft sequence—killing-green, rolling, first drying, second shaping, final firing—must finish the same day. First, 250 g batches are tossed into a 180 °C wok for three minutes of “kill-green.” The hand motion is a rapid 200-strokes-per-minute “push, flip, shake” that breaks cuticle walls without bruising tissue. Temperature is gauged by the sound: when leaf moisture flashes to steam it produces a sharp hiss the artisans call “the first cry of spring.” Next comes rolling, but unlike the kneading used for gunpowder or Longjing, Biluochun is rolled under palm pressure into a strip, then curled around the index finger to form a tight spiral. The motion resembles winding a watch spring; one lapse and the coil loosens, ruining the appearance grade.

While still pliable, the coils are scattered on a 70 °C bamboo tray for first drying. Here the leaf loses 30 % of its weight and the lake-cooled breeze carries away grassy volatiles, allowing fruity lactones to concentrate. The critical second-shaping step occurs at 60 °C: the tea master cups both palms, presses gently, and rolls the coils in a circular motion against the tray—exactly 38 circles clockwise, 38 counter-clockwise, repeated three times. This “fixed-direction rolling” sets the snail shape and polishes the surface, giving the finished leaf its distinctive white downy tips. Finally, the tea is given a 50 °C “foot fire” for 20 minutes until moisture drops to 5 %, then cooled overnight in sealed lime crocks; the alkaline lime scavenges residual oxygen, locking in fragrance.

Professional grading hinges on three visual metrics: tightness of spiral, density of white tips, and uniformity of jade-green color. Top-grade Special One (Te Yi)