Biluochun, whose name translates literally to “Green Snail Spring,” is one of China’s ten most celebrated teas, yet it remains a quiet treasure beyond the country’s borders. Grown on the mist-laden, fruit-tree-capped hills that ring East China’s Taihu Lake, this emerald-green tea is prized for its improbably tiny spiral shape, downy silver tips, and a fragrance so fragrant that, according to Qing-dynasty legend, a passing emperor once renamed it “Scary Fragrance” before court scholars diplomatically substituted the more elegant moniker we use today. For international drinkers seeking an accessible yet nuanced introduction to Chinese green tea, Biluochun offers both sensory charm and a centuries-old story of terroir, craftsmanship, and connoisseurship.

Historical Roots

Recorded references date to the late Tang dynasty (ninth century), when poets passing through Dongting Mountain scribbled odes to a tea “curled like a shell and perfumed by fruit blossoms.” Commercial production, however, stabilized only during the Ming, when Suzhou-region monks perfected the pan-firing technique that locks in the tea’s orchid-like aroma. By the Kangxi reign (1661-1722) Biluochun had become a gong cha—“tribute tea”—shipped to the Forbidden City in small, silk-lined caddies. The imperial cachet cemented its reputation, and successive generations of farmers refined both horticulture and craft to suit an increasingly discriminating court palate.

Terroir and Cultivar

Authentic Biluochun comes from two tiny peninsulas in Taihu Lake: Dongting East Mountain (Dongshan) and Dongting West Mountain (Xishan). The lake’s vast surface moderates temperature, creating morning fog that filters sunlight and encourages slow, amino-acid-rich leaf growth. Soils are acidic, quartz-infused, and laced with decomposed bamboo and loquat leaf litter, adding a subtle sweetness to the leaf. The traditional cultivar, Xiao Ye (“small-leaf”), produces diminutive buds no longer than 2 cm; modern clonal selections such as Dongting #5 yield slightly larger leaves but require exacting withering to maintain trademark tenderness. Farmers interplant tea bushes with peach, plum, and apricot trees; fallen petals contribute floral volatils that the leaf absorbs like a sponge, explaining the tea’s natural bouquet.

Plucking Calendar

The picking window spans roughly three weeks from Grain Rain (April 20) to the beginning of summer. Only the bud and the immediate first leaf are taken, ideally before 10 a.m. while dew still glistens. A skilled picker can harvest just 500 g of fresh leaf in a day; 6.5 kg of this is needed to yield 1 kg of finished tea. The earliest spring batches, ming qian (“before Qingming”), command astronomical prices because the leaf is at its most tender and amino-dense, delivering the creamy mouthfeel connoisseurs call “soup like chicken broth.”

Crafting the Spiral

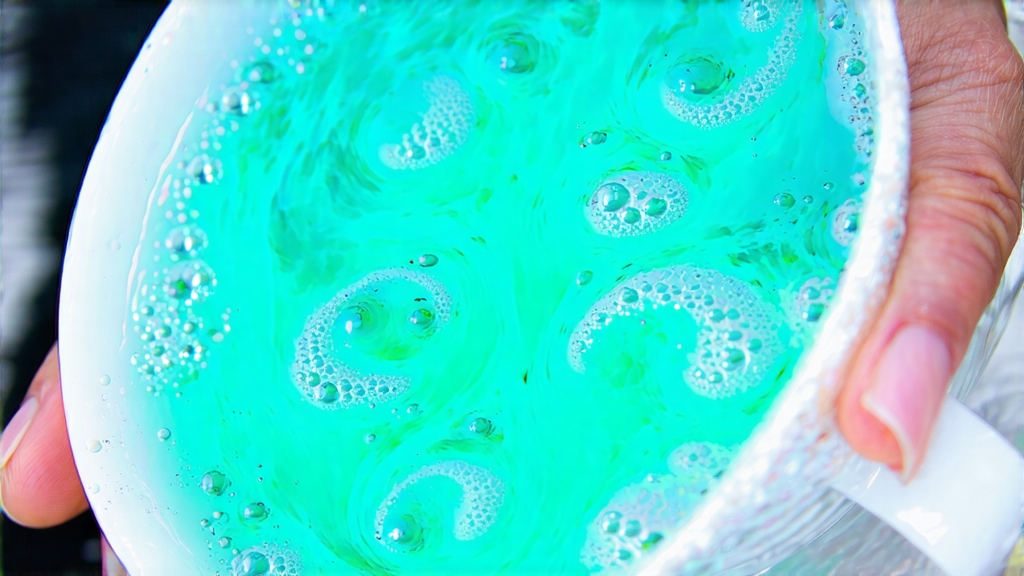

Within minutes of plucking, the leaf is spread in shallow bamboo trays and withered for two to four hours, reducing moisture to 65 % and softening cell walls. The critical sha qing (“kill-green”) step follows: leaves are tossed by hand onto an iron pan heated to 180 °C. Using only bare palms, artisans press, shake, and roll the leaf for three to four minutes, deactivating oxidative enzymes while coaxing moisture to the surface. Temperature is then dropped to 70 °C and the true shaping begins: fingers flick the leaf in a spiral motion against the pan’s rim, curling it into the snail-like form that gives the tea its name. A final low-heat bake at 50 °C for 30 minutes sets the shape and reduces residual moisture to 5 %. The entire process is completed within five hours of harvest, preserving the vivid jade color and locking in a fragrance that can fill a room even before water touches the leaf.

Grading and Styles

Although no official national standard exists, the Suzhou municipality recognizes four ascending grades: Supreme, Special, First, and Second. Supreme grade comprises >95 % buds, each no longer than 1 cm, and steeps into a pale, almost luminescent liquor. Special grade allows one leaf and one bud, delivering more body and a slightly grassier note. Lower grades include larger leaf fragments and produce a fuller, sometimes astringent cup. A separate category, “Wild Biluochun,” is harvested from seed-propagated bushes growing on inaccessible cliff faces; yields are