Long before English breakfast tables knew the word “black tea,” caravans loaded with dark, leathery leaves left the granite gorges of the Wuyi Mountains in northern Fujian. Those leaves—twisted, glossy, and impregnated with the incense of pine—were called Lapsang Souchong, the very first black tea ever created. Today, when drinkers from Moscow to Melbourne sip a smoky Earl Grey or a Russian Caravan blend, they are tasting the echo of a 400-year-old Fujian craft that began as an accident and became a legend.

Origin & Myth

The most quoted story places the birth in 1646, when Qing soldiers marched through Tongmu village, billeting themselves in tea workshops. To dry the leaves quickly for the impatient troops, farmers spread them over smouldering pine fires. The resulting tea, dark and pungent, was rushed downriver to the port of Xiamen where Dutch traders paid double the usual price. Whether myth or marketing, the tale underlines two truths: Lapsang Souchong is the archetype of hong cha (red tea, as the Chinese say), and its signature smoke was originally a pragmatic solution to wartime logistics.

Terroir: The National Park in a Cup

Tongmu and the neighbouring villages of Xingcun and Mufu lie inside the core protection zone of the Wuyi UNESCO Global Geopark. Here, subtropical mists rise from the Jiuqu (“Nine Bends”) Stream, wrapping cliffs of weathered tuff and granite. Day-night temperature swings of 10 °C slow leaf growth, concentrating amino acids and volatile aromatics. The soil is a stony laterite rich in iron and potassium; roots must dive deep, pulling minerals that later translate into a sweet, mineral finish known locally as “yan yun”—the rock rhyme usually celebrated in oolong discourse but equally present in high-grade Lapsang.

Cultivars: Beyond the “Small Sort”

The name Souchong derives from xiao zhong—“small sort”—a reference to the diminutive cultivar once dominant in Tongmu. Today, four main cultivars are sanctioned for authentic Lapsang:

- Xiaozhong (original bush, leaves barely 4 cm long, high catechin, low bitterness).

- Zhenghe Dabaicha (broad leaves, thick cell walls, ideal for withstanding heavy smoke).

- Wuyi Qizhong (a clonal selection prized for cocoa notes that marry with pine).

- Meizhan (floral, orchid-like, used for the unsmoked “new style”).

Only leaves plucked before Grain Rain (around 20 April) qualify for the top grade, Qingming Qian, picked as two leaves and a silver bud, 4–5 cm in length.

Craft: From Wok to Smokehouse

The processing choreography follows six steps, each calibrated to the weather report pinned above the factory door:

- Plucking & Sun-withering: Baskets are carried downhill before 10 a.m.; leaves are spread 3 cm thick on bamboo mats for 60–90 minutes until they lose the grassy edge.

- Indoor Withering: Moved onto slatted wooden racks in a loft heated only by mountain breeze; moisture drops to 60 % over 4 hours, edges turn chestnut.

- Rolling: A 55-minute ride in a cast-iron trough at 28 r.p.m. bursts cells without pulverising them; the juice oxidises on contact with air, scent shifting from apple to honey.

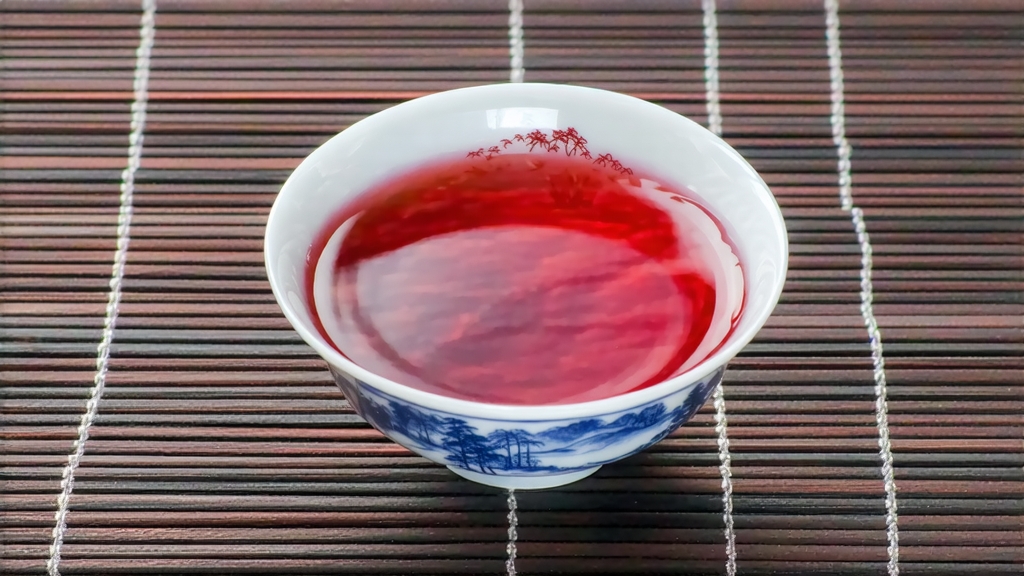

- Enzymatic Oxidation: Rolled leaves rest in cedar crates 8–10 cm deep, kept at 24 °C and 85 % humidity. Every 30 minutes a master “fluffs” the pile, allowing oxygen to penetrate. After 3–4 hours the leaf is a uniform copper-red.

- Smoking & Firing: The decisive act. A brick kiln at the base of the factory burns resinous Masson pine and local Chinese red pine; the smoke is ducted into a drying chamber where tea rests on sieves 1.5 m above the flame. Temperature is held at 80 °C for 2 hours, then 60 °C for a further 6. Volatile phenols (guaiac